As a product of parents who saw every Hollywood film released during the Depression, the local public schools, and almost all the L.A. I admit, however, to a proprietary interest in Los Angeles, the two-thirds of my total 31 years spent here blessing me with a xenophobic resentment of an outside architectural geewhizzer taking such delight in the outsized perversities slowly killing me, my friends, thousands I don’t even know, and Los Angeles itself. Moreover, Banham’s prose is an embarrassing cocktail of officialese and hip he uses or makes up ridiculous, un-euphonious slang I’ve never heard anyone here use: “San Mo” for the freeway or town of Santa Monica, “surfurbs” for the beach communities, and “autopia” for our car schtick. with eager seekers and a quick-buck economy. pop on the route of every Tanner Tour, jazzes it up with watered-down McLuhan and Robert Venturi (who are genuinely demented enough to actually like such crap), and fobs off as nutritious the same old conventioneer bullshit about “freedom” (mobility, sun, sex, affluence) for everybody which bloats L.A. Banham merely takes a quick perusal of the same old beaches, hills, plastic, and L.A. Still, the average Scarsdale demi-intellectual can tell a post-and-lintel from an arch, and the English have long been smarter than ourselves about the “States ” catapult to doom. This airy frappe of light architectural history, generalized architectural description, and fly-by-night sociology is halfway excused because it’s intended for a general, not professional, audience, and an English, rather than American or Californian, readership. What I have aimed to do is to present the architecture (in a fairly conventional sense of the word) within the topographical and historical context of the total artefact that constitutes Greater Los Angeles, because it is this double context that binds the polymorphous architecture into a comprehensible unity that cannot often be discerned by comparing monument with monument out of context (p.

In a more humane society where Banham’s doctrines would be measured against the subdividers’ rape of the land and the lead particles in little kids’ lungs, the author might be stood up against a wall and shot as it is we must try to laugh through our tears at.

Ray Bradbury, with his noxious futuro-mystical treacle in “Los Angeles Is the Best Place in America,” Esquire, October, 1972, is essentially harmless, but Reyner Banham, the English architect/pop scholar, has written a heavyweight “serious” book, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (London, 1971) which is quite dangerous because it will have a trickle-down effect (i.e., the hacks who do shopping centers, Hawaiian restaurants, and savings-and-loans, the dried-up civil servants in the division of highways, and the legions of show-biz fringies will sleep a little easier and work a little harder now that their enterprises have been authenticated).

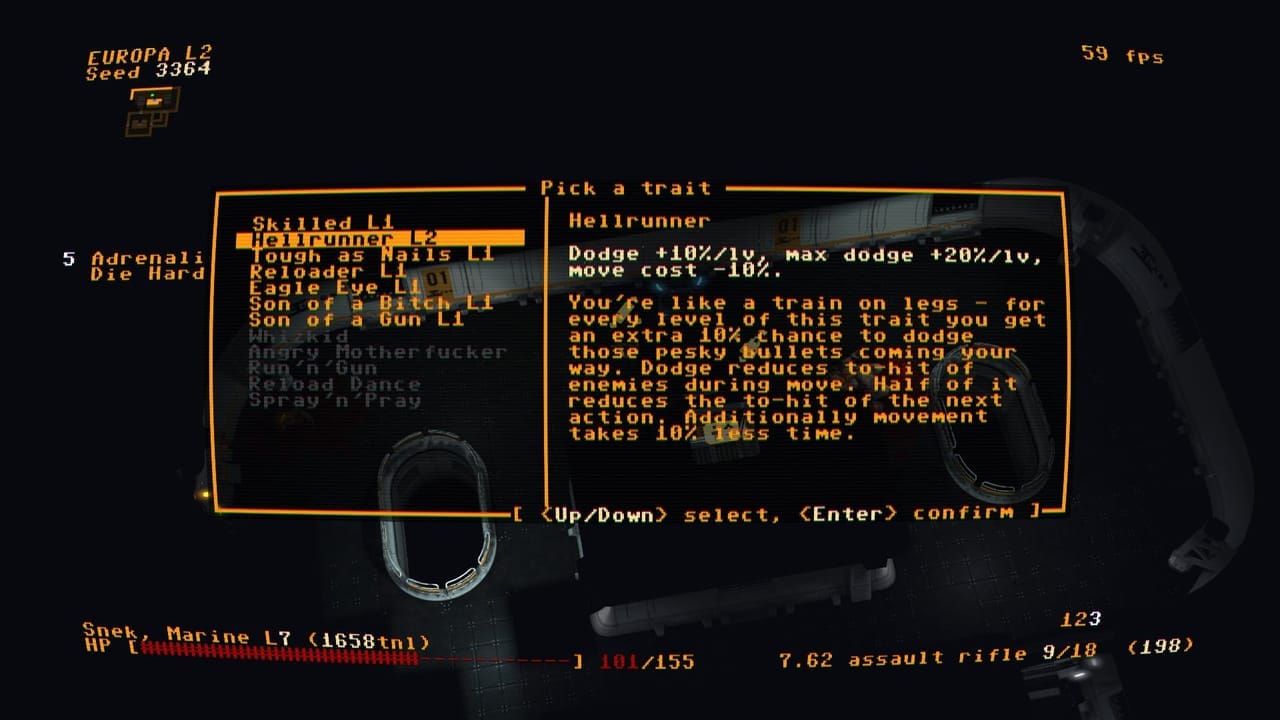

#Jupiter hell diagonal movement how to

is really a groovy place in spite of its evils and often because of them, if you know how to look at it right. mythology (“God, you don’t wanna move there now. succeeded so extraordinarily that now it finds itself plagued by a different observer: the chic debunker of current anti-L.A. In the ’60s Los Angeles moved past Philadelphia in population into third behind New York and Chicago, held the Democratic convention, acquired a spate of major league teams, built several culture palaces and 1000 miles of freeway, suffered a racial upheaval, and generally enlarged/intensified itself into the malignant tumor of a Great American City. LOS ANGELES ONCE HAD TO defend itself against snotty Eastern culture critics, English novelists, and middlebrow gossip columnists like Herb Caen who, from Provincetown-on-the-Thyroid, condescendingly refers to “that flat city down south.” The implication was always that Los Angeles, the world’s most spacious city, was in a Culture-and-Sophistication League with Dubuque, Rochester, and Provo, that it was basically “bush” and that by luck or by golly it possessed none of the brittle, knowing sophistication derived from real big city problems. Reyner Banham, Los Angeles, The Architecture of Four Ecologies (New York: Harper and Row, 1971), 256 pages, 123 black-and-white illustrations.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)